A Moffatt in France

Introduction

My story is going to cover my experience of researching my Moffatt ancestors, my work with Colin Moffat and my discovery of an intriguing WW1 story involving my Grandfather William and his brother James Moffatt, (my Great Uncle). This led me to the Royal Munster Fusiliers Association and to the author Professor Hedley Malloch, and a book Hedley is writing (publishing date summer 2019) about the” Iron Twelve” in France in WW1. Having found me as the link to the Moffatt family, an invitation was extended to me from the Mayor of Iron to attend the 11th November 2018 Armistice Commemoration service and to meet with the descendants of the families involved in the story.

My Ancestry Work: Road to Discovery!

Having a rare opportunity of some spare time, and a plea from my cousins to research the family tree, I began my work. I was reliant on conversations we had many years ago with our relatives and recalling memories, some recalled quickly others not! What I did know? That we originally came from Scotland in the mid- 1650’s at the time of the Plantation of Ireland. Our ancestors settled in County Longford and eventually also Westmeath. Having found via the internet that there was a Clan Moffat, I decided to join immediately and discovered the Clan had a genealogist Colin Moffat, who at this time was interested in tracing ‘those Irish Moffatts’. I learnt very quickly that evidence is vital, certificates necessary. Due to a piece of misinformation at the start of my journey, I began to follow a family member – but a different line! Colin in his research put me ‘back on track’ and steered me to my Birkenhead family (Great Grandfather Matthew Moffatt who moved from Ireland in late 19th century).

Using the results of my DNA test, I found my Irish cousins. After contact with them I discovered that in 2014 they had held their own ‘Moffatt Clan Reunion’ in Mullingar – nearly 70 family members attended. (I should have started my research sooner!). A booklet created by them gave me valuable family information and pictures and contacts in this country and also in Ireland.

Returning to my Birkenhead family I knew that my grandfather William and his older brother James were in the Royal Munster Fusiliers together. The younger brother John had joined The Royal Cheshire Regiment. I contacted the Royal Munster Fusiliers Association (RMF were disbanded in 1922 due to the heavy losses in WW1). A request for my home telephone number by the RMFA as they had ‘extensive’ information for me, alerted me to the fact this was not going to be straight forward. Shocked by the story that unfolded, knowing that the family were not fully aware of the whole story, I was asked by Adrian Foley of the RMFA to make contact with Hedley Malloch who was writing a book about the Iron Twelve which included my great uncle, a ‘probable’ leader of the group. They also sent me various helpful documents which I was not in possession of and aided my family history research.

The Story

Colin Moffat the Clan genealogist wrote an article in the October Moffatalia 2017 about the little known battle of Etreux and what occurred in August 1914 at the retreat from Mons. I am now going to expand on the story and fill in with a little more detail.

Hedley’s book which will be published in summer 2019 is titled: “The Killing of The Iron Twelve: An account of the Largest Execution of British Soldiers on the Western Front in the First World War. The story of the Iron Twelve and the retreat from Mons has been a well kept secret. Six hundred and fifty soldiers fought against six Battalions of Germans soldiers for 24 hours at Etreux, allowing the BEF to return to the UK. The casualties were high, and being out of ammunition 250 soldiers surrendered in an apple orchard at 9.30 pm in the evening of 27th August 1914 in Etreux. They were praised by the Germans for their ‘supreme bravery’, the odds against them were 6-1. One of those survivors was my grandfather William Moffatt who became a prisoner of war in Senne for four years.

The Sambre canal ran through the town of Etreux and James (my great uncle), was separated from his brother at this stage and the rest of the RMF by the canal. He together with four soldiers from 2nd Royal Munster Fusiliers, five 2nd Connaught Rangers and one 15th Kings Hussars retreated into the fields and woods, as so many did when separated from the main body of soldiers. Eventually they came to the village of Iron and were found and taken in and hidden and looked after by two families the Logez who owned a mill and the Chalandres who had a small farm, from the end of August 1914 to the end of February 1915. They were now deep behind enemy lines. Escape would be difficult.

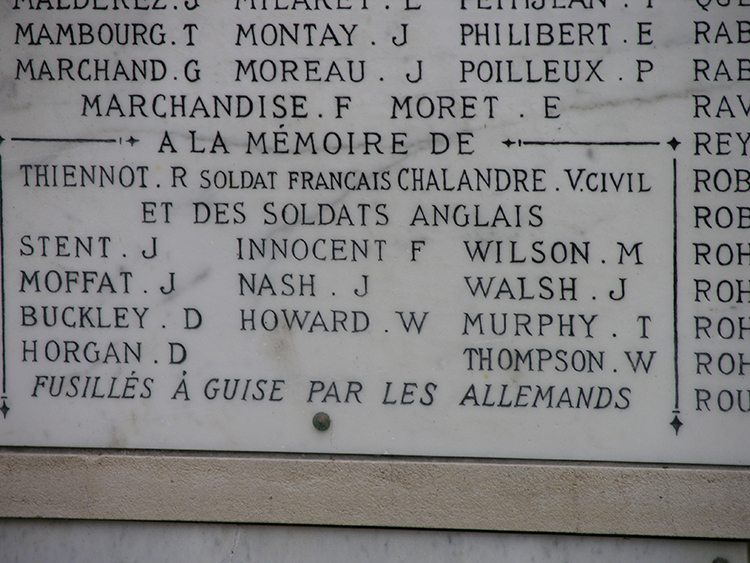

James and the soldiers in Iron were looked after well by the people of Iron. There were however two betrayals, one was in December 1914 but was a ‘botched job’ by the Germans. The second which proved fatal involved a love triangle in the village and this was in February 1915. The Germans alerted, arrested the soldiers as well as the farmer Vincent Chalandre, his wife and son and Mme. Logez and her daughter. The soldiers left quietly, in uniform, and unarmed. They were taken by cart from Iron and paraded through the streets of Guise to the cheers of the town people, who were pleased to see the British soldiers, much to the annoyance of the Germans. They were taken to the police station, interrogated, tortured and at 3am in the morning of 25th February 1915 they were taken to the top of the castle in Guise by the back entrance, and executed along with Vincent Chalandre (the farmer who hid the soldiers).

James and the soldiers had been making plans to escape. Their hideout in Iron was known to Edith Cavell, who was instrumental in getting many ‘abandoned soldiers’ in France back to the UK. Edith Cavell was a British nurse who had secured a post of Matron in a Brussels hospital. She resolved to help the British soldiers escape to Holland (a neutral country), but later in 1915 she was arrested, put on trial and executed by the Germans for aiding the soldiers. Her death caused international outrage. For James and his group their escape would have meant 31 miles of travel to the safe handover point at the Chateau in Bellingines in the north of France on the Belgium border. In Iron they were deep behind enemy lines, which made plans for their escape via Edith Cavell’s route very difficult, particularly under curfew conditions, and unfortunately this was not achieved before they were captured.

How the Story was Kept Alive

In 1919, after four years of silence for the families with regard to of what happened to the eleven soldiers, their families were eventually informed that they “failed to surrender themselves as a concealed soldier”. Of course this was not the complete story. The fact was the British Government felt the awful truth of the execution was not palatable for the families involved. Politics intervened as well, fear of retribution if this case was highlighted could have destabilised the German government, as communism was raging in Europe.

Thankfully as other soldiers returned home, the story of the soldiers in Iron was passed on. The RMF were determined not to forget what had happened in Iron. They ensured its survival by putting in print the story. After the war there were two French documents that appeared in the late 1920’s Les Onze Anglais d’Iron, an unsigned pamphlet, and a notebook by A Migrenne called Le Carnet d’un Guisard Pendant la Grand Guerre: a notebook of a Guisard during the great war which also helped to keep the story alive.

In the UK in 1928, in the World Wide Magazine, an article appeared by Herbert A. Walton called the “The Secret of The Mill”. This was a detailed account giving full details of what really happened in Iron and Guise, together with pictures of the Mme.Logez and Mme. Chalandre, of the execution site, the remains of the mill that the Germans burnt down and also miraculously a scrap of paper with the names and home addresses of the eleven soldiers, hidden under a stone near the burnt out mill and discovered later, an obvious sign the soldiers did not want to be forgotten. Another article was written in the magazine later by Derek Smith “Shot By the Enemy”. Thereafter every twenty years, details of the story were reproduced by the RMFA to keep the story alive.

In 2000 Hedley Malloch took up the baton to bring the story together in a book. He is Chair of the Memorial Fund, Honorary member of the RMFA, and taught Management in Business Schools across Europe, having been awarded a PhD by Glasgow University. Hedley’s own grandfather was in the RMF in WW1 and returned home. He had heard about this story, and when he moved to Lille in 2000 he went to Iron to continue the research, including raising funding for the memorial stone in Iron, dedicated not only to Iron Twelve but all involved in the fight for peace.

In 2014 there was a commemorative 100th Anniversary ceremony. It was attended by various French and Irish dignitaries as well as 36 members of the RMFA, including Hedley Malloch who was instrumental in fund raising for the memorial stone. It lasted most of the day visiting all the sites, including an exhibition in Etreux.They travelled from Etreux to Iron to Guise, and finished back in the ‘apple orchard’ in Etreux where the soldiers surrendered at 9.30 pm on 27th August 1914

My Trip to Iron in November 2018, for the Commemoration of the Armistice

During 2018 I had a lot of contact with Hedley to pass over information I had about James and my family, what we cousins could recall.

I had made arrangements to visit Iron with Hedley over Armistice weekend, and to attend the Commemoration service in Iron. I met Hedley and his wife Fiona in Lille and we had a full itinerary for the Sunday 11th November. We headed to the north east of France, the Aisne area, and arrived at Le Grand Fayt where in 1914 the army commenced defending the Sambre canal, whilst retreating from Mons. A memorial stone commemorates this site where the battle started on 26th August 1914. The Germans by this time were on the opposite side of the Sambre canal eventually cornering the RMF in Etreux, as the bridge in Etreux had not been blown up. The message from HQ not to hold the line and to retreat did not get through to the soldiers. Their Officer Major Charrier therefore had decided they must continue to defend and fight. They could have retreated as they were at least half an hour ahead of the Germans, but instead fought bravely against overwhelming opposition.

We then drove on to Etreux Cemetery, originally the apple orchard where the dead soldiers were buried. The land was purchased at the end of the war by the parents of a British soldier. This was handed over to the War Graves Commission and is maintained by them today. Granddad (William Moffatt) was now a prisoner of war until the end of 1918. A.W. Awdry (of Thomas the Tank Engine fame), lost his brother here in the battle. A look over the cemetery wall, towards the Sambre canal and it was easy to imagine the Germans bearing down on the town, which must have been a frightening sight.

We continued on to Iron for the Commemoration Service in the Civic Hall at 11.30, for all who fell in WW1. All French soldiers lost, including the British soldiers, had their names read out followed by a personal message from the President. The French national anthem followed: La Marseillaise.

We were stood by the Civic Memorial and the memorial stone dedicated to the Iron Twelve which are placed next to each other, and laid our wreaths and remembered those lost. We felt it was important that they were not forgotten and we should ensure that they will always be remembered. The monument to the Iron Twelve was carved by a firm called Feelystone in Roscommon Ireland, and the bronze plaque was designed by Seamus Connolly in Ireland, there by maintaining the connection with Ireland. Inside the Civic Hall champagne and cake was served, and we met members of the Logez and Chalandre family. Afterwards we were invited back to the home of a member of the Chalandre family for more champagne and lunch. (Excellent!) There we sat, grandchildren and great grandchildren of the people involved in the tragic story, French and British remembering them.

Afterwards we saw the site of the mill and farm which were burnt down as an act of reprisal against the French village, their incomes being lost. The Germans had removed every nut and bolt from the mill and sent it to Germany. Then on to the cemetery in Iron to see the graves of the two women who looked after the soldiers, Mme. Logez and Mme. Chalandre and daughter Germaine.

From Iron we travelled on to the town of Guise, to the Police station where the soldiers were interrogated along with members of the Logez and Chalandre family. The soldiers were tortured and then taken at 3 am in the morning on 25th February 1915 to the top of the Chateau in Guise and executed, together with Vincent Chalandre the farmer. The village suffered greatly by the loss of the mill and farm, and the two families involved were imprisoned, with devastating consequences to various family members. The principal German Officer deciding their fate was the Kommandant in Etreux, Richard Von Waechter.

After this, we visited the civic memorial in Guise where the Iron Twelve are remembered along with the French soldiers of both World Wars. From here we then had a trek up to the Chateau in Guise – the chateau is built on a hill and has now been taken over by a local history society. It was not lost on me that Mary of Guise was the mother of Mary Queen of Scots, who married James V of Scotland. At the entrance to the chateau there is a board dedicated to the British soldiers and explaining what happened to them. The Chateau is partly in ruins, referred to in a previous article in the 1920’s as ‘grim’, years later I felt it was forbidding, not a pleasurable experience. I was only allowed to go onto the execution site at the very top of the chateau on my own, with a volunteer and the resident guard dog (not on a lead or tethered!) which didn’t add to what was a poignant moment for me.

Lastly we visited Guise cemetery to lay wreaths and sprays. There is a communal grave dedicated to the soldiers. In 1920 the bodies were dug up from the execution site in the Chateau and reinterred in a communal grave in the cemetery. Vincent Chalandre was buried separately, but buried with military honours. After the war the British Government awarded Vincent Chalandre a silver medal and two bronzes were awarded to the Logez, mother and daughter, and to the Chalandre mother and son for their bravery in hiding the soldiers, a letter accompanied was written by Lord Curzon.

Summary

My research brought me in contact with many people from different countries and different walks of life. I could not have believed from the start of my research how much I would discover about my Moffatt family, and what resources came to me. I would encourage everyone to research their family trees, and pass down to and involve the younger generations their family history. Record what you find. Never has ancestry as a subject been as popular as it is now. You don’t know what you are going to uncover and learn, and there will be varying surprises along the way as I have found. What did I learn from my weekend away and research, don’t give up on the family research however daunting. I have learnt that despite our personal feelings and different cultures, these don’t divide us, what is more important is human compassion and understanding the impacts of disloyalty and betrayal, overcoming these to discover the truth.

Alison Parfitt

March 2019