The Soldiers

We are always anxious to hear from any descendants of the eleven British soldiers who stayed in Iron.

ABBREVIATIONS:

1/CR The First Battalion, Connaught Rangers

2/CR The Second Battalion, Connaught Rangers

1/RMF The First Battalion, Royal Munster Fusiliers

2/RMF The Second Battalion, Royal Munster Fusiliers

3/RMF The Third Battalion, Royal Munster Fusiliers

BEF British Expeditionary Force

Acknowledgements

What follows are the brief biographies of the eleven. During the Blitz German bombs destroyed ten of the soldiers’ service records. Like every other researcher of First World War soldiers, I have had to work around this very large crater in the record. The biographies have been compiled from surviving military records (e.g. medal index cards, soldiers’ wills, medal rolls, etc.), census returns, newspaper clippings, local and regimental histories, prison records, interviews with the soldiers’ descendants; and genealogy sites, both geographic and familial.

I would like to pay special thanks to Tom Moffatt, Jeremy Fatherton, Paul-Anthony Byrne, Janet Arrowsmith, Margret Oakley, Mike Riordan, Oliver Fallon of the Connaught Rangers Association, and Adrian Foley of the Royal Munster Fusiliers Association for the help they have given me. Many on the Great War Forum answered my questions about these soldiers and the British army to which they belonged; amongst the many members of that Parish to whom I owe a particular debt are Tom Burnell and Martin G. Of course I alone am responsible for all errors, omissions and exceptions.

The eleven soldiers sheltered by the Logez and Chalandre families in Iron were part of the British Edwardian Army. This was composed of volunteers, unlike its German and French counterparts both of whom conscripted young men to their ranks. Between 1902 and 1914 men signed up for varying periods, but in principle their service was split between time in the colours and time in the reserves. Colour service was a posting on active service, to a depot in Great Britain, or to garrison some outpost of Empire in Asia or Africa. Once service in the colours was completed the soldier would be transferred to the reserves. They were sent home to resume their civilian lives, but could be recalled to the colours should they be required to do so. There were many variations in the system, but after 1906 a common arrangement was for a man to sign a contract for 12 years, seven or eight years to be spent in the colours followed by four or five years in the reserves.

In August 1914, of the eleven soldiers in Iron, five were regulars and six had been recalled from the reserves, proportions roughly in line with that of those of the BEF as a whole. Their average age was about 27, very similar to that of the BEF. The oldest was aged 34, the youngest, 19.

The eleven joined the Army in various ways. In general, the Irishmen signed up at a depot in Ireland belonging to the regiment of their choice. The Englishmen appear to have been recruited by personnel sent by the regiment to tour the industrial towns of Great Britain in search of recruits. Two of the older Irish soldiers joined by the militias. These were an early forerunner of the Territorial Army, amateur in many respects, but offering training and summer camps to their members. They were a valuable feeder for the Victorian army. The militias, very strong in Ireland, were gradually phased out in the first decade of the twentieth century.

Lance Corporal James Moffatt, 2/RMF. A reservist. A second-generation Irishman, he was a Roman Catholic and he was born in Liverpool. He was the leader of group who appears to have been a troubled figure with problems in accepting authority. He was a multiple deserter from His Majesty’s forces, first from the Royal Navy, and later from the Cheshire Regiment. He joined the Munsters in late 1903, possibly as a reaction to a terminated love affair. He enrolled in the company of his brother Tom. James joined 1/RMF; Tom went into 2/RMF. It is possible that James went to 1/RMF because at that time they were in India and he needed to escape the attentions of the Royal Navy and the Cheshire Regiment, both of which may have been looking for him. James served in India and Burma before returning home sometime in 1911 or 1912.

When war was declared he was working in Hunslet, Yorkshire and he was mobilised into 2/RMF as at that time 1/RMF were still in Burma. There he was reunited with his brother, Tom. Both fought at Etreux. Tom was captured and spent the rest of the war in a German Prisoner of War camp.

Private Denis Buckley, 2/RMF. A reservist. At 34-years old he was the oldest and one of the most experienced of the eleven soldiers. He came from the Shandon area of Cork, a district that housed the city’s busy docks. His father worked as a general labourer, as did Denis prior to his recruitment into the British army. His mother was semi-literate. Denis joined the army in December 1898, first in the Royal Munster Fusiliers’ Militia. He transferred to the regular army in August 1899. After the militia he was placed in 3/RMF, a training battalion for soldiers who would later be posted to either 1/RMF or 2/RMF. Denis was allocated to 1/RMF in in February 1899. Shortly afterwards he went with them to South Africa arriving to fight in the Boer War.

By 1914 he had more than made up for his lack of stature by virtue of his service in the field. Denis grew up quickly, actively participating in some of the hardest fighting in the Veldt, most notably in the defeat of the Boer forces at Bethlehem. He served throughout the entire South African campaign and was awarded the Queen’s South African medal and the King’s South African medal, with a total of five clasps each awarded for his participation in particular actions and campaigns in this war.

In 1902 his battalion left Cape Town for India to garrison the North-West Frontier. There Denis endured the normal hazards associated with this theatre of operations: skirmishes, long marches made in fierce heat, fire-fights, the attentions of snipers and cholera. In March 1912 1/RMF left India and were transferred to Burma. One of his comrades was James Moffatt. Sometime between 1911 and 1914 he was released from the colours to the reserves. At the outbreak of war he was lodging and working in Cork City. Like Moffatt he was recalled to 2/RMF rather than 1/RMF who were still in Burma.

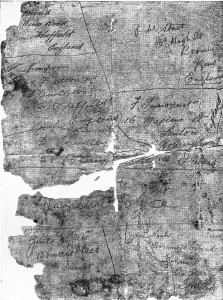

Shandon, Cork City from St. Patrick’s Bridge: 1910. Both Denis Buckley and Daniel Horgan were born and grew up here.

In summary Denis was a medal-laden, ‘old sweat’, battle-hardened on the South-African Veldt and on the North-West Frontier of Pakistan. He vastly experienced and used to operating in hostile terrain. His is a complete contrast to his fellow soldier from Shandon, Denis Horgan.

Private Daniel Horgan, 2/RMF. A regular, and at 19 years old he was the youngest of the group. His family lived in the slums of the Shandon district of the town. It was a rough area with poor living conditions as evidenced by its appalling infant mortality rates. Daniel lived with his parents and two siblings in one room in a tenement. His father was a semi-literate, poorly paid dock worker employed on a casual basis in the nearby docks. Daniel was relatively fortunate. In 1911 he was 16-years old and working as a messenger boy. In early 1912 he joined the RMF. The sole surviving fragment of his Army attestation papers give his occupation as a general labourer. As with many of the Irish soldiers, it is difficult to believe that his family’s straightened economic and social conditions did not form part of his decision to enlist.

This photograph is believed to be George Howard in uniform. The photographer’s backdrop of a water mill appears as a ghostly apparition, as a portent of the tragedy that was to end his life. (By kind permission of Margaret Oakley)

Private George Howard, 2/CR. A regular. George’s father was Elijah Howard; his mother was Jane Howard, Elijah’s second wife. George was one of their six children, the middle boy of three sons, Arthur and William being his two brothers. Elijah, Arthur and George worked at the Cornish Place Works of James Dixon, one of Sheffield’s leading cutlers. George was a fork and spoon cutler.

Elijah, George’s father, was a ‘little mester’ or a specialist subcontractor who worked for the bigger firms such as Dixon’s. Both George and Arthur worked for their father in the Spoon and Fork department at Dixon’s. Throughout the first decade of the twentieth century pay and working conditions gradually declined in an industry which, in any case, had a very bad record of health and safety at work.

George was both working for, and living with, his father and his better-paid elder brother. Life may have been a little claustrophobic for him. Little encouragement may have been needed for him to join the Connaught Rangers when they came to Sheffield to recruit in 1908. It is not known why he chose the Connaught Rangers. The Howard family were not Roman Catholics, neither had they any known Irish family connections.

The war was viciously cruel to the Dixon family. Arthur, George’s eldest brother and co-worker, joined the Royal Engineers and was fatally wounded on 1 July 1916 during the first day of the battle of the Somme. He died the same day. He left a 25-year-old widow, Rosina, and two young daughters, Edna and May.

James Dixon & Sons War Memorial. Unveiled at the Cornish Works, Sheffield in 1926, it bears the names of both George and Arthur Howard. (Courtesy of www.picturesheffield.com)

His youngest son, William, joined 8/East Yorkshire Regiment. He was hit by a shell during the battle of Arras and evacuated to a hospital at the British army infantry base at Etaples near Boulogne. He died there on 2 May 1917.

Private William Thompson, 2/CR. was another regular from Sheffield. He was the eldest of nine children, comprising seven boys and two girls, born to Emily and William Thompson. Before his enlistment in 2/CR in October 1908, he had followed in his father’s footsteps and worked as a forgeman in one of the many Sheffield steelworks. This seems to have been the family’s trade: at least two of his brothers, Harry and John worked as forgemen, too. As with George Howard there is nothing in his family history to indicate why he chose an Irish regiment in which to enlist. He was not a Roman Catholic and had no known Irish family connections. When the Connaught Rangers recruitment team came calling to Sheffield in October 1908, he may have found the lure of Ireland stronger than that of furnaces.

There were always strong trading links between Sheffield and the USA. Workers also crossed the Atlantic to help service the links helping to commission furnaces and rolling mills, to train workers, and to practice their trade. The Thompson family were part of this American trade and they had spent some time in Pittsburgh. William had a reputation as a crack-shot and was a member of the Battalion rifle-shooting team. Both William and George Howard trained and served in Ireland in Tipperary, Fermoy and the Curragh, until 24 September 1913, when 2/CR were transferred to Aldershot.

Private John Walsh, 2/CR. A reservist and the second oldest soldier in the group, and the most highly decorated of all the soldiers in Iron. He was a native of Tullamore, King’s County, Ireland, home of the eponymous whiskey. He, his four brothers and one sister seem to have been brought up without a father in the house.

In many ways his early history in the Connaught Rangers is similar to that of Denis Buckley of 2/RMF. He enrolled in the Connaught Rangers at Tullamore in January 1899 for seven years with the colours and five with the reserves.

On 9 November 1899 he sailed with his regiment for Cape Town. For the next three and a half years he participated in all of the actions involving the Connaught Rangers. These included the relief of Ladysmith, anti-guerrilla operations in the Transvaal, the Orange Free State, and Tugela Heights. It was not an easy war for 1/CR. In particular, they lost heavily in the fighting for Ladysmith. He returned home to Ireland hen the Boer War ended in 1902. He was awarded the Queen’s South Africa Medal with five clasps, and the King’s South Africa Medal with two clasps. His service with the colours expired in January 1906 and he drops out of view from this time until August 1914.

News of the Walsh family and of John’s disappearance on the retreat to the Marne surfaced in the local Irish papers when his mother, who had been reduced to penury, appealed to the Board of Guardians of Tullamore Union for relief. At the time of her claim, John was hiding in the Chalandre house at Iron. Mrs. Walsh told the Board that she was destitute and despite the fact that she had three sons at the front ‘fighting for Empire’ she had received absolutely no support from the Government or anyone else. All she had to live on was two shillings worth of provisions given to her by some ladies of the town, and she had nothing with which to pay the rent. At this point she told the Board that she had a received a letter from the War Office telling her that one of her sons could not be found and they surmised that he was a prisoner of war. This missing son was deemed to be John. The story that he was a PoW was a red herring that was to cost Mrs. Walsh dear in the years to come. The Board promised to write to the War Office on her behalf noting ironically that, ‘It is a capital encouragement to young fellows to join the army to leave their mothers starving.’ The confusion as to John’s real identity was not cleared up until well after the war.

John was not one of the original group of nine soldiers found in the fields by Vincent Chalandre. He was one of the two soldiers found by Clovis Chalandre on 6 or 7 December. His comrade on the run was the next soldier, Private Matthew Wilson

Police in Ahascragh c.1900. (Courtesy National Library of Ireland)

Private Matthew Wilson, 2/CR. A reservist. Matthew was born in 1884 in Ahascragh, a poverty-stricken village in eastern Galway.

Matthew was a member of the Connaught Rangers’ militia when he joined their regular army regiment at Galway in December 1900. He was just 16-years-old, but he lied about his age on enlistment by stating he was 18-years-old. Like all of the other Irish soldiers in this story he gave his occupation as that of a labourer. He joined the regiment at the Renmore Barracks, Galway, served for six weeks, and then on 24 January 1901 he promptly went absent without leave, leaving his uniform, arms and equipment behind, taking only his army haversack.

Four days later he presented himself at the Leinster Regiment’s depot at Birr, King’s County, and enlisted in that regiment under the name of Thomas Runor, his new family name being his mother’s maiden name. The army seems to have been remarkably relaxed about what could be construed as desertion. His only punishment was 72 hours hard labour. In October 1903 he was included in a draft of 79 soldiers sent from Ireland to reinforce 2/CR in Ahmednagar in the State of Maharashtra, India. Later he transferred to Poona.

His service in India was marked by two distinct and contrasting tendencies: one was to indiscipline and the second was to self-improvement. In the five years he was there he was charged seven times for minor misdemeanours, most of them drink related. His punishments were not severe being small fines and usually a week’s confinement to barracks. Shortly after arriving in India he contracted gonorrhoea resulting in over two months in hospital. His problems with health and alcohol were common to soldiers posted to India. Life in the Indian barracks was dull. Because of the heat the working day started and finished early. Parades commenced before sunrise, lasted for about two hours and unless the soldier was on duty he had nothing to do for the rest of the day but amuse himself. Their favourite diversions were alcohol and sex. The abuse of both was widespread, systemic and institutionalised. Alcohol was so cheap that in effect each man could have as much as he wanted; consequently binge drinking was common. Sexually transmitted diseases were rampant and at the end of the nineteenth century nearly one in two British soldiers in India were infected.

In other words, Matthew’s dalliances with sex and a liking for alcohol were not abnormal. Quite the opposite: sex and alcohol and their consumption were established parts of the culture of the British army in India in which he was immersed. On the other hand, the British army did offer opportunities for personal improvement and development in the form of training programmes and Matthew appears to have taken advantage of these. Between 1904 and 1906 he successfully took courses in reading, writing and arithmetic and was eventually awarded a 2nd Class Army Certificate of Education. This achievement signified a good grounding in an elementary education. At the same time he passed the Army’s Advanced Nursing Certificate, which meant he was the first port of call for any Connaught Ranger with minor cuts, bruises and ailments. These skills may have been useful in the Logez mill and the Chalandre attic. It is clear from his record, too, that someone in a position of authority saw some leadership qualities in him. He was appointed Lance Corporal in September 1906, but his elevation did not last long. Following two drink-related disciplinary offences in November 1906 and in January 1907 he was reduced to the rank of Private.

Matthew left India at the end of 1908, returned to Ireland, and was placed in the reserves. He did not stay long in Ireland, emigrating to St. Helens, England where he found work as a coal-miner. On completion of his four years in the reserves in 1912 he re-engaged for a further four years. When war came he was posted to 2/CR in Aldershot and landed with them in Boulogne, France on 14 August 1914.

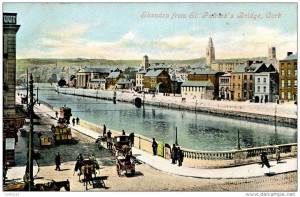

Edith Stent at the collective grave of the eleven British soldiers.

Lance Corporal John Stent, 15th (The King’s) Hussars. A regular. His father worked as Head Gardener at Albyfield, Bickley, Kent, the palatial home of John Scott, a wealth London textile merchant. He was the second and last child of John and Elizabeth Stent. Edith, his sister was seven years his senior. The family lived in the Lodge House of Albyfield. Today his early childhood home survives today as The Bickley Manor Hotel. He joined the 19th Hussars toward the end of 1906, but sometime after 1911 he was transferred to C Squadron of the 15th (The King’s) Hussars. He landed in Rouen on 18 August 1914. Once there his squadron was attached to 1 Division. On 27 August 1914 he was fighting with the Munsters near the village of Bergues in the Thièrache.

His sister, Edith, was an important figure in the dissemination of the story of the Iron 12. In the late 1920s she visited Iron, probably in the company of Herbert Walton, a journalist. His version of the story appeared in The Wide World magazine in 1928. Edith married in 1916 and her husband, Harold, was killed on the Somme in the autumn of that year. She subsequently remarried to Fred Pryke, a hussar in the 15th (The King’s) Hussars and a friend of her brother’s. Edith appears to have died childless in the 1930s.

Private Terence Murphy, 2/CR. A reservist aged 28 years old. He was the only one of the eleven soldiers who was married. Terence is known to have had one child, William Terence, who was born on 4 August 1914, the day before his parents were married. He was a stone-cutter with a criminal record for robbery and assault when he enlisted in 1/CR in 1905 or 1906.

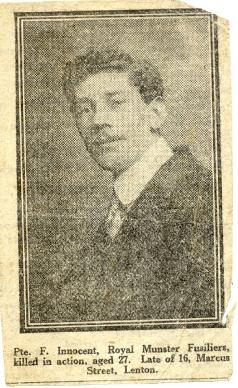

Fred Innocent. (Courtesy of Janet Arrowsmith)

He deserted shortly after enlistment but was recaptured. He would have gone with 1/CR to Malta in March 1907, and ten to India. He probably returned to Ireland towards the end of 1913 on the expiration of his time in the colours. His brother Joe was killed at Passchendaele in the closing days of the battle of 3rd Ypres in November 1917. He was serving with 2/RMF.

Less is known of the remaining two soldiers.

Private Frederick Innocent, 2/RMF. A reservist. He enlisted in 2/CR in 1904 in his home-town of Nottingham. By 1911 he had returned there and was working as a clerk in a wine merchants at the time of his mobilisation. Fred was the eldest of six children born into a working class family in Nottingham. His younger brother John (known as Jack) enlisted with the Royal Berkshire Regiment. He was injured and captured in 1916 and spent the rest of the war as a POW. Fred is the only one of the eleven soldiers for whom an authenticated photograph survives.

Private John Nash, 2/RMF A regular. He was aged 21 and was one of nine children born to James and Bridget Nash, in Sneem on Rossmore Island, a beautiful and remote part of County Kerry. The men of the family worked as road builders. John is believed to have worked in England prior to his enlistment in 2/RMF in the summer of 1913.

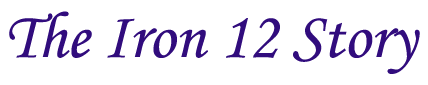

Below is a copy of a piece of paper on which the soldiers wrote their details. The quality is not good but you can make out the writing made in each of the soldier’s own hand. It contains nine names and not the eleven you’d perhaps expect. There is a good reason for this. We know from the story that nine were found in the fields by M. Chalandre. Two were found later on; possibly early December 1914. The missing names show that the list was written before that date and the late arrivals were Wilson and Walsh. In the case of Fred Innocent and in all probability, the rest of the nine, this is the only copy known to exist of their own hand writing.

We think it is unlikely, as claimed, that Mme Logez 'found' the list in a bottle buried in the woods. She probably asked the soldiers to provide the details. In all probability she then took the list, put it in the bottle and buried it in case the Germans found it at the farm or mill.

2 December 2015