BEHIND THE LINES: THE STORY OF THE IRON TWELVE

PART 3: THE AFTERMATH

Bachelet’s Fate

Bachelet’s treachery was not yet finished. He told his German masters all he knew concerning the whereabouts of other Allied soldiers on the run and in hiding around Iron. Consequently the Germans mounted manhunts in the area during which an unknown number of Allied soldiers ‘in hiding, who were waiting for the return of the French Army, or for a chance to escape to Holland, were hunted, taken and shot.’ He took his 120 francs reward for the Iron captives, but it seems to have brought him little consolation. He returned to live in Iron where he was despised, rejected and reviled by the locals. On occasion he appears to have been badly beaten up by them. He complained to the German authorities who did nothing. He was captured and taken into custody when the Allied armies returned in September 1918. He was loathed so much that his captors refused him food. He was transferred to a military prison in Châlons-sur-Marne where he died in custody whilst his case was being investigated, apparently from natural causes. In another account Bachelet is reported as being found dead on arrival at the military prison. However he died he maintained to the end that the men he had denounced to the Germans were not soldiers on the run, but ‘deserters who had got what they deserved’.

The Logez Family

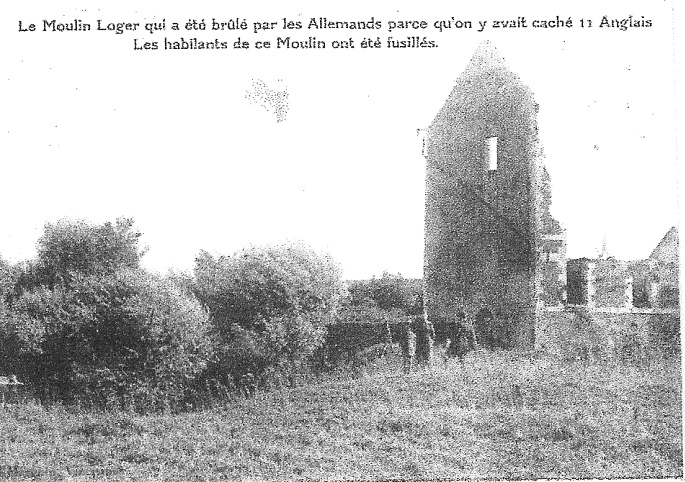

Madame Logez was sent to Delitsch prison which appears to have been an important incarceration centre for French women convicted of helping British soldiers. There she was, in her own words treated like a criminal ‘and herded with murderers, forgers and thieves. We suffered greatly from the damp, and it sends a shiver through me today to think of the food we were forced to eat. … I was ill most of the time I was at Delitsch. It lasted more than three years and a half – a purgatory that only ended with the Armistice’. Her daughter, Jeanne went with her to the same prison. Madame Logez’ husband was forced onto the streets where he lived on neighbours’ charity until his death shortly afterwards. When Walton visited Iron in the mid to late 1920s he found that Madame Logez had re-married and was now Madame Griselin. The Griselins were trying to rebuilt the mill burned by the Germans, but had had to abandon their efforts due to lack of funds.

Caption: The remains of the Logez mill in the 1920s. Burned by the Germans as part of their reprisals against the Logez family, the mill was never rebuilt.

The Chalandre Family

The three youngest Chalandre children, Marthe, Marcel and Leon were turned out onto the street where, according to one account, ‘they existed by begging until the armistice’. Clovis served his sentence in Rheibach prison, near Bonn; his mother and sister Germaine went to Siegburg, near Cologne. Here the Chalandre women found conditions similar to those experienced by the Logez women in Delitsch. Madame Chalandre’s health deteriorated to such an extent that she was spitting blood. She was released with her daughter in 1917 and returned to Iron where they were reunited with the three youngest children. The events of February 1915 and what passed subsequently had severely depleted them all. The health of all of the young Chalandre children was broken. Clovis, released after the Armistice, seems to have been unhinged by his experiences and became mentally ill. Madame Chalandre died in July 1919 and the burden of looking after the four children fell on Germaine. Marthe was spitting blood; Leon ‘was much weakened by congestion of the lungs’. Smith reports that both Marcel and Marthe subsequently died.

Germaine took on the role of provider for her younger siblings. She gained employment in the Paris office of a US company, the Equitable Trust Company of New York and taught herself typing and shorthand. In April 1922 she won a major competition sponsored by l’Instringeant for the most deserving Parisienne worker, after being nominated by her fellow employees. She won 40,000 francs, furniture and a car. In 1928 she married a M. Delchez. She returned to Iron after the Second World War and saw out her days there.

Edith Stent’s Visit to Iron

Walton reports that Stent’s sister, Mrs. Pryke, had visited Iron and met the Logez family. Miss Stent had married Fred Pryke of Bromley, Kent and he too served in the war as a soldier in the 15th (The King’s) Hussars. According to the 1901 Census Stent had one sister, Edith, a school teacher. She was seven years older than her brother. Walton does not give a date for the visit, but the evidence suggests that it was made between 1920 and 1927. Edith took away from Iron a curious and important memento of the incident. After the events, Madame Logez had found in the ruins of the mill a handwritten list of the names and addresses of nine of the soldiers. It had been hidden under a stone. Madame Logez gave this list to Edith and it is now lost but a copy of the original is shown in the Gallery section and on the Soldiers' page.

The Award of PoW Helpers Medals to the Logez and Chalandre Families

Recognition from the British government to Logez and Chalandre families came in September 1920. In brief, after the war two new medals, silver and bronze, were created for Belgians and French who had helped British PoWs behind the lines. The Foreign Office (FO) ran the awards system – British military intelligence identified names to British Ambassadors who made recommendations to the FO. The FO had a wider remit than PoWs in Belgium and France, notably British and non-British civilians in neutral countries throughout the world. The effect of this wider brief was to absorb the two PoW helpers’ medals into a civilian honours’ hierarchy of medals, Empire awards, medallions and letters of thanks. The FO made this wider range of awards available to PoW helpers: they were now eligible for a range of decorations and medals, and not just the two new medals. The hierarchy of awards was as follows:

- CBE and letter of thanks

- OBE and letter of thanks

- Silver medal and letter of thanks

- MBE and letter of thanks

- The Medal of the British Empire and letter of thanks

- Bronze medal and letter of thanks

- Letter of Thanks

A full description of how this system developed can be found in The National Archives as can a full list of the awards made to PoW helpers. This more liberal approach was not as open-handed as it first appeared. In the relevant file there is a concern to restrict the number of British Empire awards awarded to non-British subjects and to close the lists of those eligible as quickly as possible. Certain awards were rationed. For example, there were to be only two CBE awards made available to PoW helpers and the number of bronze and silver medals was limited to about 100 and 500 respectively.

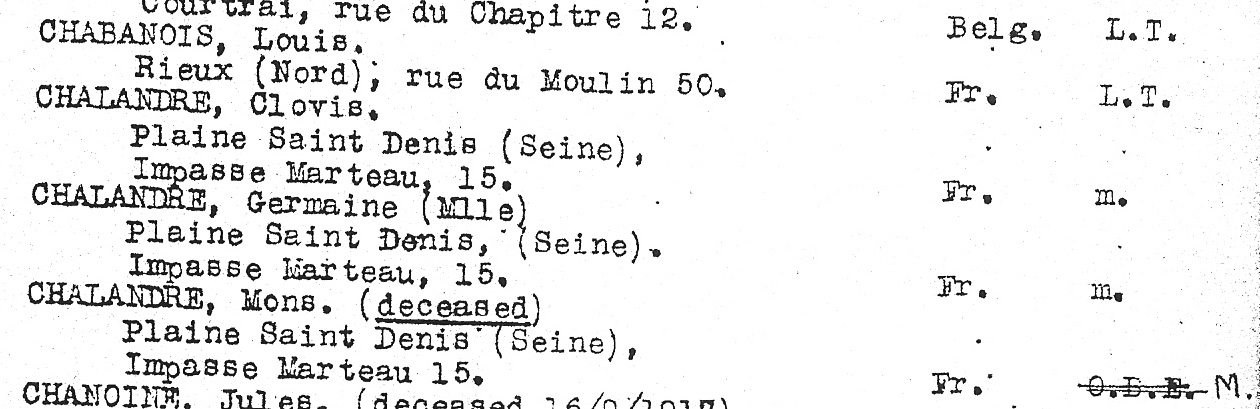

A total of five were made to the two families most concerned. Two bronze medals went to the Logez family, one each for mother and daughter. Three were awarded to the Chalandre family: a silver medal to Vincent Chalandre; a bronze medal to his wife daughter – and a bronze medal for Clovis. An extract from the list of awards made to the Chalandre family is shown below:

Caption: The Chalandre Family’s entries in the Prisoner of War Helpers Medal List. The lower-case ‘m’ means a bronze medal; the capital ‘M’ signifies a silver medal. O.B.E. means Order of the British Empire.

There are two points concerning the awards made to the Chalandre family, which require explanation. The first concerns Clovis’ bronze medal. According to Walton and Les onze Anglais it was his lack of intelligence and weaknesses which helped to condemn the soldiers, the Logez family, killed his own father and, indirectly, his own mother and two of his siblings. How could he be considered eligible for a PoW helpers medal? The most likely reason is that the bronze medal was a blanket award made to all helpers who had been imprisoned by the Germans, and that British military intelligence did not enquire too carefully into the circumstances of each case before passing on their findings to the relevant Ambassador.

The second concerns Vincent Chalandre’s award. The scratched out O.B.E award indicates that he was one of only 16 French and Belgian citizens considered for this award. He and two others seem to have been disqualified from this award because they were dead and this award was not made posthumously. Vincent Chalandre demonstrates his courage and dedication to the Allied cause to such a level that it qualifies him for one of the highest honours in the British honours system, but he is debarred from that very award because those self-same acts result in his death before a German firing squad. Vincent was the victim of a Catch-22 of which Joseph Heller would have been proud. The inability of the UK government to recognise fully his valour is a direct outcome of a decision to bestow honours which were inappropriate for what was, in effect, military type service. It is clear from the relevant file that this was due in large part to the Army Council’s reluctance to give military awards to civilians.

It also appears from the British records as if Germaine Chalandre and Léonie Logez suffered an injustice in that their services to the eleven would seem to merit a silver medal rather than the bronze they received. Dame Adelaide Livingstone who worked in the British Embassy in Brussels spelled out the criteria for the award of the higher award, the silver medal. In a letter to Sir Frederick Ponsonby, one of the Palace’s eyes and ears on this part of the honours system she wrote of the gold medallion – which later became the silver medal.

… the gold medallion [silver medal] is to be given in reward for very considerable services; indeed I am told that it is never to be given except in cases where the recipients have risked their lives by sheltering our prisoners during the German occupation in their own homes by giving them food and assistance at a time when they themselves were practically starving. (Letter written by Dame Adelaide Livingstone, Chief of War Office Special Mission to Sir Frederick Ponsonby, 14 January 1920).

The Chalandre and Logez ladies appear to have met all the relevant criteria for the award of a silver medal. There appears to be no rational reason why they were awarded the lesser recognition of a bronze medal.

Exhumations and Re-interments

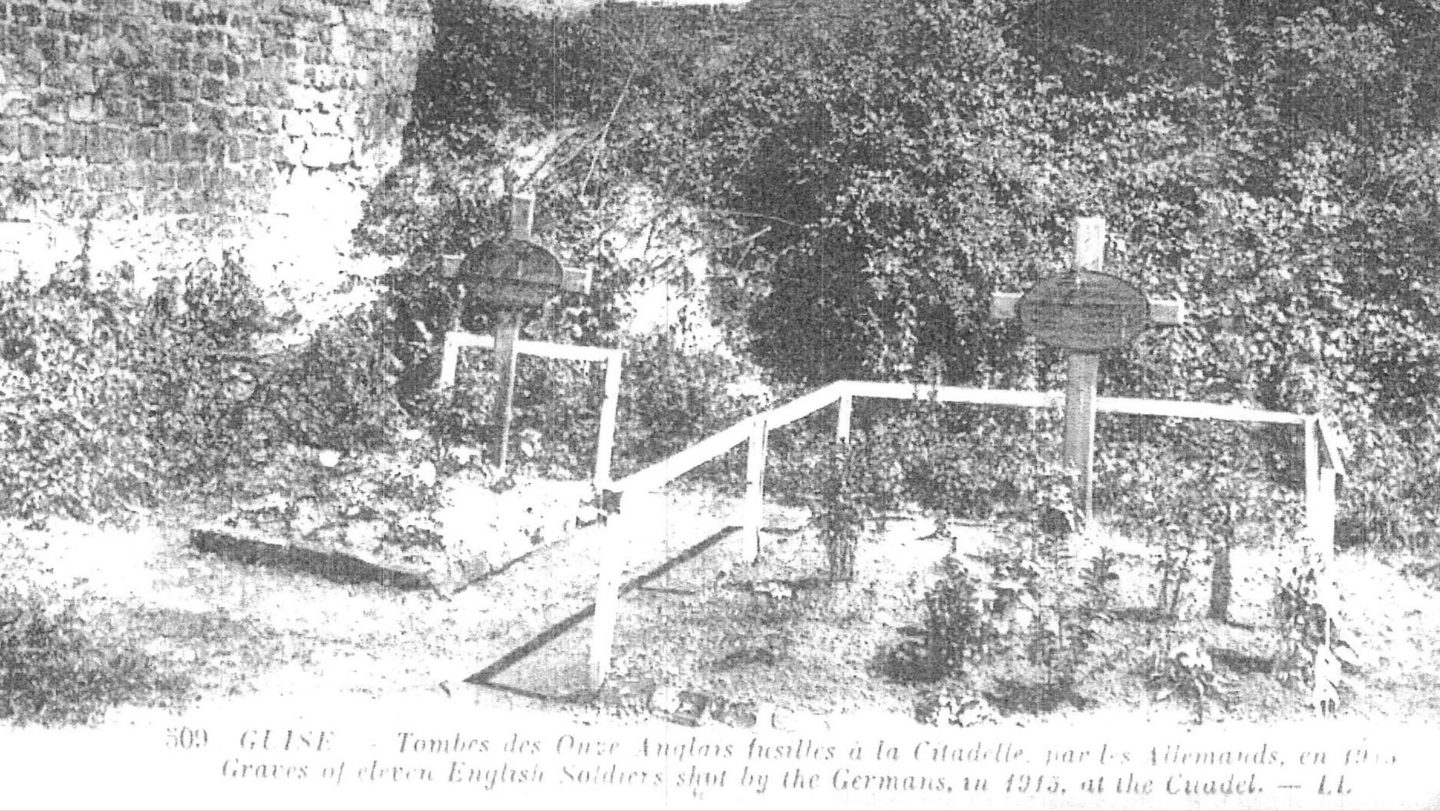

Caption: The original burial plot in Guise Château. The twelve were buried where they were shot, in two batches of six. This photo was taken in 1919 or 1920.

The bodies of the eleven soldiers and M. Chalandre were exhumed in May 1920. The soldiers’ remains were placed in four coffins. Individual identification was not possible except in the case of M. Chalandre who was distinguished by his civilian clothes, and one of the British soldiers, thought to be Fred Innocent, who was wearing a medallion. The coffins were draped in a Union Jack and interred in a collective grave in Guise Communal Cemetery under CWGC care where the soldiers are appropriately commemorated.

Chalandre was interred a few yards away. Today his grave is totally unmarked and utterly neglected. How and why the grave of a French hero, considered by the British government to be amongst the very bravest of the French and Belgian civilians to have helped Allied soldiers trapped behind the lines, has come to this pass must be a matter of serious concern. It seems likely that it is in part connected with the aftermath of the events of February 1915 which killed his wife, two of his children, and sent a third mad. They swept away his family and with them went those who most likely to ensure that his memory was preserved.

Caption: The collective grave of the eleven British soldiers. Above and to the right the brooding tower of the château, their place of execution.

THE UNANSWERED QUESTIONS

Smith’s account of events in Shot by the Enemy ends with two unanswered questions. These are:

Was there a twelfth British soldier who escaped the clutches of the Germans?

Why did the soldiers stay in Iron rather than try to escape back to the UK?

The Story of the Twelfth British Soldier

This is recounted in Harry Beaumont’s account of how he escaped from German-occupied Belgium back to England. Beaumont met another fugitive whilst they were both sheltering in Edith Cavell’s clinic. The second soldier was called Michael Carey, a Munster Fusilier. The story Carey told Beaumont was that Carey had been one of a party of twelve Munsters sheltered by a miller at ‘Hiron’. There they had worked for him in return for his kindness until dawn one morning when the Germans had raided the mill. The British soldiers and the miller had been tried on the spot and shot within an hour. The mill had been burned to the ground and the miller’s wife and family had been transported to Germany. Carey had been spared this fate because of a sudden inclination to leave his bed and visit friends on a neighbouring farm. There he stayed the night, returning to the mill next morning to find only the remains of a smoking ruin, and to learn of the unhappy fate that had overtaken his former comrades and benefactor.

This is clearly the same incident and Smith argues that while there are many inconsistencies there is some support for it in the form of one of the older residents of Iron who said that as a young man he had heard of an escapee. Yet when Carey’s account is compared with other accounts it receives hardly any verification. The soldiers belonged to three regiments and not one; they were taken by the Germans in the afternoon and not at dawn; at the time of their capture they were sheltering in Chalandre’s house and not at the mill; it was Chalandre’s house and not the mill that was the first to be burned; the twelve were not tried and executed on the spot; and the miller (Monsieur Logez) was never implicated in the affair.

There are other unsatisfactory aspects. His name does not feature on surviving accounts of the list taken away from Iron by Edith Stent. The ease with which Carey suggests that he could come and go from his hiding place does not ring true. To clarify matters for this research M. Gruselle was asked if he had heard of another escapee in the village. He said that as a young man he had heard of one. He was then asked if a twelfth man had ever been discussed in his family. His reply was emphatic: ‘Non, c’était toujours les onze’ – ‘no, it was always the eleven.’

If there had been a twelfth man then the Logez family would have known about him. There would have been good reason to be silent about him during the war but that would have vanished with the Armistice. Then there would have been many reasons to talk about him and to celebrate his survival. His escape would provide a ray of light in an otherwise bleak picture. The fact that he was never discussed in the Logez family is conclusive proof that there was no twelfth man. Carey knew a garbled version of the incident. He may even have been hidden in Iron, but at no time was he part of the group.

There is a warning in Carey’s story for all students of the Western Front: because a personal account is vivid, exciting and recounted with conviction, this does not mean it is true. There is a whole genre of very persuasive Western Front literature based on little other than the personal testimonies of survivors of the sort given by Carey to Beaumont. Carey’s account reminds us that the test of these stories is not interest, drama, emotion or danger, but whether or not it can be verified.

Why did the Soldiers stay in Iron?

M. Gruselle was asked if he could shed any light on the soldiers’ motivation for staying in Iron. He said that as a young man he had known older villagers who had met the soldiers and discussed the soldiers’ plans with them. According to these sources the soldiers decided to stay where they were and await the return of the Allied armies. With the benefit of hindsight it can be seen that that view was untenable, but in the winter of 1914-15 it had some foundation. Iron is roughly halfway between Ypres and the Marne. The soldiers would have been able to hear the guns of the armies as they fought down to the gates of Paris; and then again as they pounded their way back to the North Sea coast. While there was gunfire there was hope. The battles of 1915 such as Neuve Chapelle, Aubers Ridge and Loos, which would show the rigidity of the Front, lay some months ahead. Then there was the general expectation that this was a war which would be over by Christmas. There were many external reasons why staying put made sense.

On the other hand, there seem to have been few internal forces to move. The soldiers had all experienced life in the chill outdoors of the forests and fields. It is now impossible to understand the social dynamics of the group, but there does not appear to have been any the eleven who had either the formal authority or the charisma to impose any alternatives on the group.

Successful escapes did take place, but mainly in the early months of the war. Les onze Anglais reports the escape of thirty-five Englishmen from northern France to Holland, organised by ‘an admirable woman, Mademoiselle Louise Thuliez’. Lyn Macdonald reports two similar mass escapes, admittedly in the immediate aftermath of battle. Once the Front settled down the Germans tightened their grip on the rear-zone and escape became increasingly difficult throughout 1915-16. In 1915 escape networks in Lille and Brussels were broken by German intelligence, and their organisers executed, notably Philippe Baucq, Edith Cavell and Eugène Jaquet. In early 1917 the German army withdrew to the Hindenburg Line, only a few miles from Iron. When that happened the front line moved to the back door and the German control tightened considerably making escape all but impossible. McIntyre reports two attempted escapes at about this time from Villeret involving three British soldiers. Both failed. In truth the chances of a successful escape for the eleven became increasingly faint from the end of 1914 onwards. From that point the only alternative to hiding was surrender.

CONCLUSIONS

One conclusion relates to the precarious nature of ventures such as the one described here. On the whole communities like Iron held firm in the face of German threats: they erected a wall of silence behind which Allied soldiers could shelter. Yet the lesson from Iron was that ‘on the whole’ was not good enough. It only took one person to inform for the soldiers to be handed over to the Germans. The motive was not usually money. Lust, jealousy, anger or mental instability seem to have been much more important. By nature these are both unpredictable and volatile and they made ventures to conceal Allied soldiers a hostage to a fickle, but ultimately malign, fortune.

Episodes such as this force a re-appraisal of what the ‘Western Front’ means. It was not defined by the front line – what happened behind the lines was important. Whilst it has always been recognised that ‘behind the lines’ was important in the sense of logistics, engineering and communications supporting the troops in the trenches, this case suggests that what was happening behind enemy lines was significant. The players were different and the occupying power certainly had very different concerns. This aspect of the Western Front has been neglected. For example there is no memorial for those who would not surrender. Nor is there one to the civilians who helped them. As this story shows they paid for their courage with their lives. In broadening the scope of the Western Front new actors emerge. Women take on a new role; children too young to serve in the trenches have parts in this drama. This is a positive development. This is written in the months after the death of the last soldiers to serve on the Front; and many of us who knew them are no longer in the first flush of middle-age. Memory of the Western Front is at a critical juncture. It stands a much better chance of surviving if it encompasses a wider cast and broadens its geographic scope. It can do both by more fully embracing stories such as this one.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author gratefully acknowledges the help given by the following: Paul Crowther and Karine Sbihi for help with translations; Paul-Anthony Byrne for sharing his materials and his interest; André Gruselle, the Mayor of Iron; the Willeman family of Iron, the staff at St. Ménard Cemetery, Guise; the staff at TNA, Kew; Roslalind Guillemin at Guise Château; David and Janet Arrowsmith and the family of Fred Innocent; Bill Morris and the family of John Nash; and to my wife, Fiona, for proof-reading and an inexhaustible supply of ironic metaphors and witty similes of how some men define women’s wartime roles. Last - but by no means least - to Derek Smith and the Royal Munster Fusiliers Association who kept this incredible story alive. Of course the author alone is responsible for all errors of fact and