BEHIND THE LINES: THE STORY OF THE IRON TWELVE

PART 2: THE ELEVEN BRITISH SOLDIERS IN IRON

The Soldiers Arrive in Iron

The first contact came on 15 October 1914 when Vincent Chalandre came across nine British soldiers in the fields near Iron, a small village of 500 souls about three miles to the south of Etreux. The soldiers, still in possession of their rifles, were scavenging for raw carrots and other root crops. They asked Chalandre for bread. Chalandre was a retired silk weaver living in Iron but he worked as a casual labourer for Monsieur and Madame Logez, smallholders who owned a mill in Iron. Touched by the plight of the nine, reduced to rooting in the fields for vegetables, Chalandre resolved to help them. Monsieur Logez had suffered a stroke and appears to have been mentally incapable; in these circumstances Madame Léonie Logez had taken over the running of the family business. As well as her husband, she had a son, Oscar, aged 16, and daughter Jeanne, aged 15, to help her.

Cometh the hour, cometh the woman. For Walton, who met Madame Logez several times as part of the research for his article he was:

Caption: Iron today: much diminished in population the village is otherwise little changed from 1914.

greatly struck by her boundless energy even after the cruel trials that she suffered as a result of her devoted care to the British soldiers. It was a rare experience to listen to this wonderful French woman as she recalled in a most matter-of-fact way, how she responded to M. Chalandre’s request for aid: “ How could I do otherwise than help these poor fellows who were lost and starving?” she asked. “It was my simple duty.” … She set about the task of saving the pauvres enfants, as she continually called them, with rare resolution.

Les onze Anglais describes her as a ‘dynamic woman and a good patriot’. Her first response was to organise shelter for the nine soldiers in a large hut belonging to her, located in fields she owned. This was very dangerous as there were Germans billeted in the village. Despite the risks involved she organised food supplies for them, using her cover as a smallholder who owned cows. She took soup and bread hidden in a milk bucket to the hut in which they were hiding. She raised no suspicion with the resident Germans, whom she often met on her errands of mercy to the fields. This arrangement lasted for five days. On October 20 the weather deteriorated and Madame Logez decided that the nine soldiers should take a hot supper and spend nights in her mill, a little to the north of the village. By day the soldiers would return to the hut in the fields very early in the morning, returning only at nightfall. This system continued until 1 November when it was decided to split the sleeping accommodation. Five soldiers should sleep at the mill; four would go to Chalandre’s house in the village itself.

Whether they were in the hut or at the mill, Madame Logez remained responsible for feeding them. Her smallholding enabled her to move around carrying meat and cereals; her mill gave her access to flour, which she used to bake bread for the soldiers. She organised a network of women, rendezvous and pick-up points to furnish the considerable supplies demanded by the daily task of feeding the nine soldiers. In this she was helped by Vincent Chalandre’s ‘brave wife’, their ‘heroic’ daughter Germaine, aged 20, and a Madame Vigèle who secured them clothes, milk and food. A Mme Jules Dufour also helped; she ferried food and other supplies from the house of a woman who had died during the invasion. Madame Logez, Madame Chalandre and Germaine remained responsible for taking the food to the soldiers in their hut. Madame Chalandre had four other children apart from Germaine. These were: Marthe, aged 14; Marcel, 10; Leon, 7; and Clovis, 16. It was Clovis who, on 6 or 7 December discovered two more British soldiers hiding in the woods. Madame Logez accommodated them with alacrity observing only that, ‘If I can keep nine, I can keep eleven.’

The first portent of doom arrived on 15 December when forty German military police arrived on motorcycles at the mill. Madame Logez, displaying considerable bravery and nerve, delayed them just long enough for her daughter, Jeanne, to warn the soldiers who were asleep in the loft to escape through the rear. They managed to get clear of the mill, crossed the river and hid in a copse on the other side. The Germans surrounded and then entered the mill. They searched it and found nothing save some flour and supplies, and no indication of the English presence. Walton states that the soldiers used this escape route ‘frequently when in danger of discovery’ which suggests that this was not the only occasion the soldiers had a close call. In a small, tightly-knit community, where many people were related and where most people knew a great deal about other people’s business, many must have known of the presence of the soldiers amongst them. It is possible that the raid of 15 December was the result of information received by the Germans. On the other hand Madame Logez appeared to think that it was a ‘perquisition,’ or compulsory confiscation of food and supplies, which the Germans routinely exacted from the French communities they occupied. As a result of this close shave it was decided that the mill was too dangerous and that all eleven would stay at Chalandre’s house, whilst Léonie Logez would continue to be responsible for feeding them.

The Betrayal

In the village lived a woman named Blanche Maréchal. She was married and she was generous with her sexual favours. Her lovers included German soldiers, or as Les onze Anglais puts it, ‘the Germans, too, wallowed in this filth.’ Another was Clovis Chalandre, the 16-year-old son of Vincent Chalandre. There was some very indiscreet pillow talk during which Clovis told her about the British soldiers. Blanche told her husband who made his own enquiries, and he stimulated gossip. One way or another the news reached one of Blanche’s other lovers, Bachelet, a 66-year-old veteran of the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71.

Clovis, who appears amply to justify Les onze Anglais’ description of him as a ‘stupid youth’, was jealous of Bachelet. On the night of 21 February Clovis went to M.Maton’s brasserie where Bachelet lodged and threw stones at Bachelet’s window. Bachelet’s response shocked Clovis. Bachelet shouted, ‘You’ll pay for this; tomorrow I am gong to inform on you and the English – you will all be shot!’ Clovis returned home – and told no one. Bachelet was to be as good as his word.

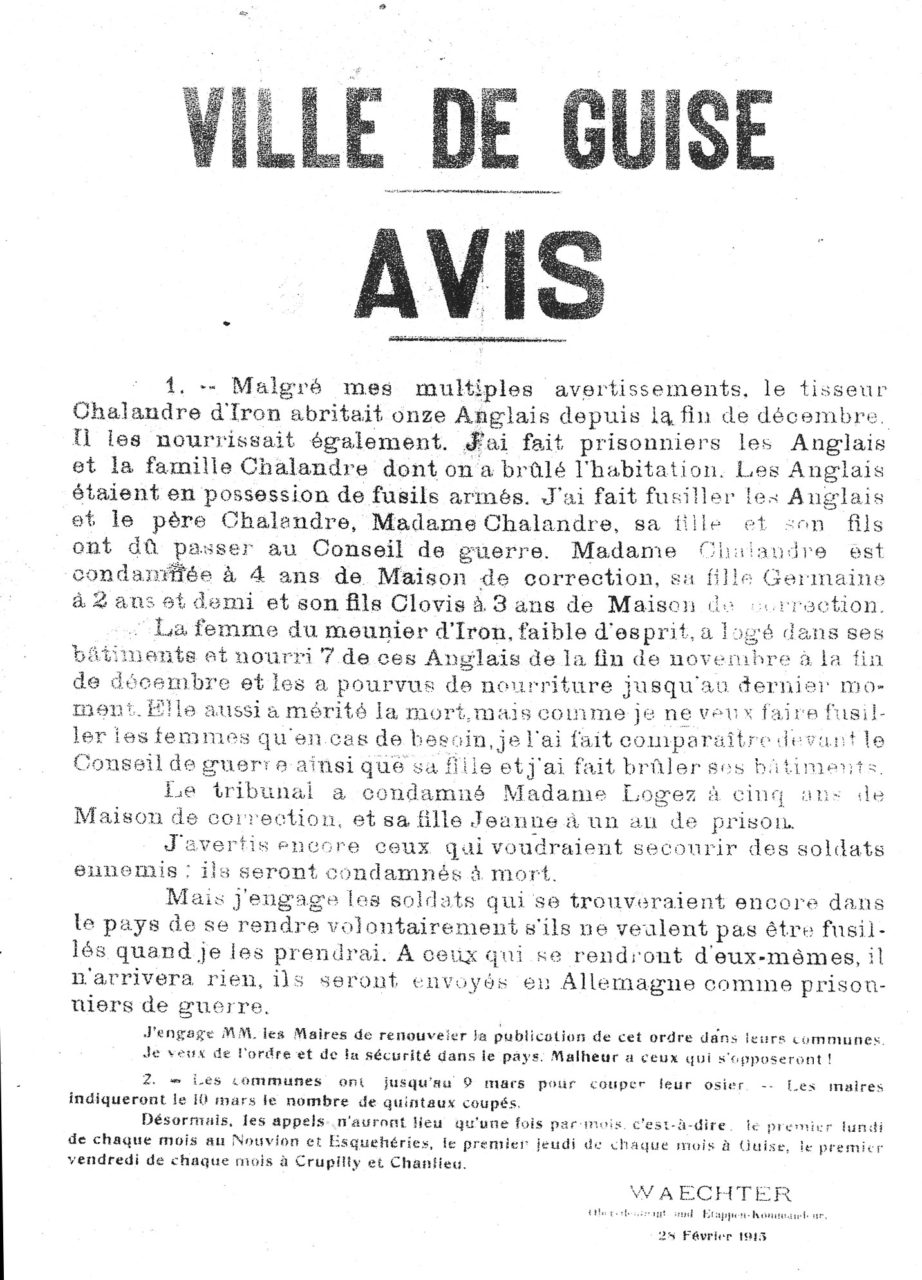

On 22 February Bachelet, driven by ‘a thirst for revenge, and a madness born of senility’ went to the German military headquarters in Guise. There the Rear-Zone Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Waechter and his adjutant Kolera, received him. To these two Bachelet denounced the soldiers and those who were sheltering them. On the same morning Madame Logez, who suspected nothing, went to the same German military HQ. This was a regular visit she made to renew her trader’s pass, a permit which allowed her to move around freely. This document was usually granted to her without question, but this time she was greeted very coldly and told that she would have stay there until the evening. The German military HQ was unusually busy. While she was waiting, through an open door she saw Waechter and Bachelet in the next room. Bachelet blanched when he saw her and he indicated that he did not wish to say any more in front of her.

The Capture

Waechter began his preparations to take the British troops. All that day German troops passed up and down the road between Guise and Iron. In the afternoon Waechter and Bachelet boarded a small convoy of two cars and a lorry in La Place des Armes in Guise and set off for Chalandre’s house in Iron.

The arrival of the German troops was witnessed by one of the Logez ladies, probably Jeanne. Years later she told Walton:

We realised that when we saw the road suddenly covered with Boches that the crisis had come. I tried as I had done on the first occasion to warn the soldiers … but it was impossible to do anything for they had been told where they would be likely to find the men.

On arrival at Chalandre’s house Bachelet and Waechter got out. Without hesitating, Bachelet opened the door of the house. He saw Chalandre who was in the yard and said to him, ‘I want you to know that I have sold out you and the English! … Let that be a lesson to you for feeding deserters!’

The eleven soldiers were in Chalandre’s large attic busy washing themselves and repairing their clothes or shoes. They had guns and about 1,000 rounds of ammunition between them. They could have fought the Germans, but they went quietly, perhaps reasoning that any resistance on their part would only lead to reprisals against the villagers. The Germans tied their hands behind their backs, and then bound them in pairs. Along with Chalandre, they were punched, kicked and beaten into the waiting lorries. According to Les onze Anglais at least one was slashed on the thigh with a sabre. Before they left the Germans torched the Chalandre family home and all their possessions. The villagers were forced to witness the incineration.

The soldiers were then taken to the German HQ in the Guise Town Hall located then, as now, in rue Chantraine. At Madame Logez’ suggestion, a story had been agreed, in case of just such an eventuality. This said that the soldiers had been in Iron for a week; before that they were living rough and stealing their food. They knew neither the mill, nor the Logez family. It was only Chalandre who gave them food to eat, and then only for payment.

Next day, 23 February, Mrs. Chalandre, her daughter, Marthe, and her son, Clovis, were arrested. They knew the cover story, but Clovis could not keep to it and he told the Germans everything he knew, thus sealing the fate of soldiers and civilians alike. Madame Logez was arrested on the evening of the 23 February and brought to Guise Town Hall. There she was beaten up, and imprisoned in the open yard for two nights, next to where the British soldiers were held. Whilst she was in detention the Germans returned to Iron and burned her mill to the ground again in front of the assembled villagers. The farm’s poultry was killed on the spot by the Germans, loaded into two lorries and taken away.

Guise Town Hall in the Rue Chantraine. It was here that Madame Logez witnessed Bachelet’s betrayal of the British soldiers, and where they were brought after their capture and held until their execution. Since 1915 the façade has been cleaned and renovated, but its interior remains much the same. The neighbouring houses whose inhabitants were disturbed by the screams of the British soldiers can be seen on the left of the Town Hall.

At this point a curtain descends. The German record, if it exists, cannot now be traced. Les onze Anglais claims that the twelve did not receive a trial or any form of hearing have to be regarded with scepticism; indeed, Les onze Anglais contradicts itself on this point later quoting a newspaper report stating that the soldiers had received a trial, albeit a mock one. Another source speaks of the soldiers passing before ‘a hastily convened military tribunal.’ It is likely that the soldiers and Chalandre were given some sort of hearing. Otherwise why wait two days? A public mass execution in Iron immediately following the arrest, with a blazing family home as a backdrop, would have been a very impressive demonstration of German power and resolve.

Observed German practice in similar cases supports the idea that the twelve were put through some type of formal hearing. For example there were three British soldiers arrested in St. Quentin at about the same time, and there is the well-documented fate of the four British soldiers at Le Catelet. These seven soldiers received a military trial before sentence and it is likely that the British soldiers and Chalandre went through the same process. On the other hand, Waechter issued a lengthy public statement after the execution of the soldiers, in which he makes no reference to a trial or hearing; he simply states, ‘that I had them all shot’.

The Execution

According to one newspaper report, the soldiers were badly beaten up on the night of 24-25 February, to such an extent that their cries woke the residents of Rue Chantraine. On the morning of 25 February the twelve were woken and subjected to ‘a terrible beating with punches, whips, cudgels; blunt instruments and rubber hammers in an orgy of joyous and strictly administered callous cruelty’. Half-conscious, the twelve were put in a cart and taken into the Château at Guise by the porte de- secours, a gate at the rear of the castle specially built to allow the admission of reinforcements in times of crisis.

Caption: The relief gate, Guise Château. It was through this gate that the British soldiers and Chalandre were led to their place of execution on 25 February 1915.

On the other side of the relief gate a ditch had been dug. Everyone understood its significance. The soldiers were made to stand along the edge of the ditch in two batches of six. The youngest of the soldiers spoke briefly. His last words were: ‘Let’s pray – chins up. Remember – Englishmen were never slaves. No-one can say that.’ Then the soldiers saluted. The order to fire was given twice; gunfire rang out and the Englishmen were mown down and fell into their communal grave where a German soldier gave them the coup de grace. Their bodies were then covered with soil.

At least this is the account given in Les onze Anglais and by Walton. It is not wholly true since, on exhumation, the soldiers’ hands were tied behind their backs thus rendering the act of the final salute impossible. Similarly exhumation revealed that only Chalandre of the twelve had been give a coup de grace. These errors beg the question as to how much of the rest the account of the execution is the product of a fertile imagination rather than detached and objective reporting.

Caption: The execution site at Guise Château today

Whether or not the British and Chalandre received a hearing, the members of the Logez and Chalandre family were brought before a military tribunal. Madame Logez’ life was spared. She was given five years’ imprisonment, Jeanne, her daughter, one year’s imprisonment, Oscar, her son, was sentenced to penal servitude for an unspecified period. Madame Chalandre was sentenced to four years’ forced labour; the Chalandre children Clovis and Germaine respectively drew three years and two-and-a-half years’ hard labour. Their sentences were served in German prisons.

Explaining the German Reaction

Whether or not a trial took place, the Guise executions were calculated, deliberate and carried out in cold blood. The executions were large in terms of numbers; certainly nothing equivalent in size has been traced. They may not have been illegal, but they were harsh and this raises the question of why the Germans reacted in this way.

Occupying Germans had a choice as to how they handled captured Allied soldiers and their helpers. The death penalty was by no means automatic; discretion was possible at every level. Macintyre highlights several interesting cases, including one in which an eminent French lady hid two British troops whilst simultaneously playing hostess to several German officer lodgers. Her relationship with one of the German officers appears to have been intimate. Eventually the two British soldiers tried to escape, were captured and promptly denounced her to the Germans. One of the officers told his hostess that ‘her friends’ had been caught, but no action was taken against her.

Not all caught soldiers were executed: the two soldiers in the previous incident appear to have been spared. McPhail cites a case of three who were betrayed in St. Quentin; two were shot, but the third was packed off to a PoW camp in Germany. Even a death sentence did not necessarily lead to an execution. Private David Cruickshank of the 1st Battalion of the Cameronians was taken in by a family at Le Cateau and remained undetected for two years. He was captured and sentenced to death in October 1916. His protector, a Madame Baudhin, was tried with him. Her son had been killed earlier in the war in the French Army. She saved Cruickshank’s life with an impassioned appeal to the judges that: ‘the cruel battlefield has already robbed me of one my sons … God has sent this British boy in his place.’ Following her plea Cruickshank’s death sentence was withdrawn and replaced with 20 years’ imprisonment.

Caption: The notice issued by Waechter announcing the execution of the Iron 12 and the reprisals taken against the Chalandre and Logez families. A place in a PoW camp is offered to any allied soldier surrendering voluntarily, but death for thoseFrench people found sheltering them. His stark statement that he had shot all the soldiers and Chalandre contrasts with the more detailed description of the fate of the French civilians, prompting speculation that the 12 had been executed without trial.